Ο εξαιρετικός ιστότοπος AmynaGR είχε γράψει παλαιότερα ένα πολύ ενδιαφέρον άρθρο για την απειλή των Τουρκικών βαλλιστικών πυραύλων εναντίον στόχων όπως οι αεροπορικές βάσεις της ΠΑ. Σε αυτό γινόταν σαφές ότι η δυνατότητα της Τουρκίας να καταστρέψει μία αεροπορική βάση (κατά βάση τα καταφύγια αεροσκαφών και πυρομαχικών) ήταν μηδαμινή δεδομένης της ακρίβειας των βαλλιστικών της πυραύλων.

Στο άρθρο αυτό θα αναφερθώ στο ίδιο ζήτημα από μία λίγο διαφορετική οπτική, ορμώμενος από μία αντίστοιχη εργασία της RAND για την απειλή της Κίνας εναντίον των αεροπορικών βάσεων της USAF στην περιοχή του Ειρηνικού. Η μελέτη της RAND δεν εξέταζε (μόνο) την ικανότητα συνολικής καταστροφής μίας αεροπορικής βάσης αλλά ενός πιο περιορισμένου (χρονικά και χωρικά) στόχου, της άρνησης λειτουργίας της για ένα περιορισμένο χρονικό διάστημα (πολεμικών) επιχειρήσεων.

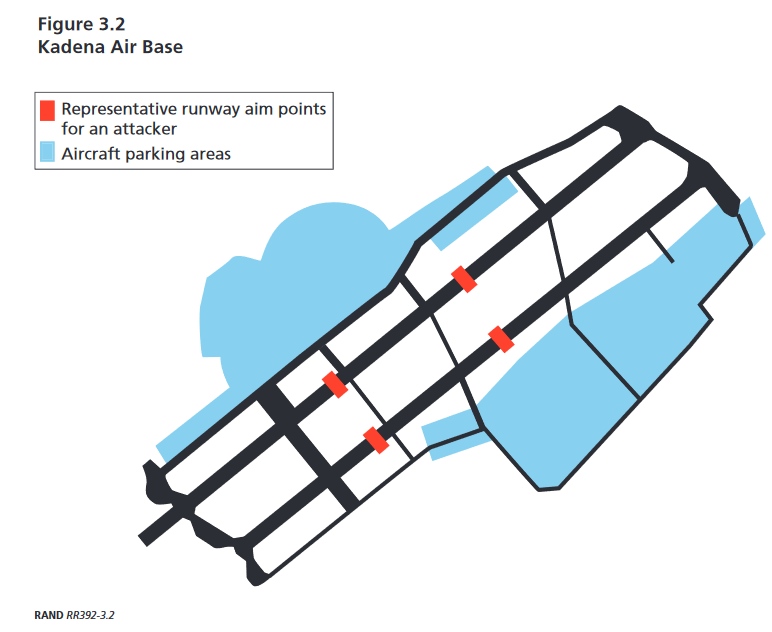

Για το σκοπό αυτό η Κίνα θα έβαζε ως κύριο στόχο τους αεροδιαδρόμους μίας βάσης με σκοπό να προκαλέσει πλήγματα σε συγκεκριμένα σημεία τα οποία να αποτρέψουν την εκτέλεση απο/προσγειώσεων μαχητικών (και άλλων) αεροσκαφών μέχρι την επιδιόρθωση των ζημιών. Μία ανάλογη επιτυχία της Τουρκίας εναντίον ενός αρκετά περιορισμένου αριθμού κύριων βάσεων της ΠΑ θα έδινε την αεροπορική υπεροχή στην Τουρκική αεροπορία για ένα περιορισμένο χρονικό διάστημα, εντός του οποίου θα μπορούσε να επιχειρήσει την καταστροφή των βασικών μέσων αμύνης της χώρας (ραντάρ, Α/Α μέσα, αεροπορικές βάσεις) χωρίς την απειλή εχθρικών αεροσκαφών και πληγμάτων στα Τουρκικά αεροδρόμια με τελικό στόχο την καταστροφή της ΠΑ στο έδαφος.

Προκειμένου να εξετάσουμε την πιθανότητα επιτυχίας μίας ανάλογης επιχείρισης θα χρησιμοποιήσουμε ως στόχο την αεροπορική βάσης της Τανάγρας. Η βάση έχει έναν κύριο διάδρομο με μήκος περίπου 3 χιλιόμετρα και πλάτος 45 μέτρα. Με βάση τις ελάχιστες αποστάσεις για απογείωση/προσγείωση αεροσκαφών είναι απαραίτητο να επιτευχθούν 3 πλήγματα σε διαφορετικά σημεία με ακτίνα περίπου 20 μέτρων το καθένα. Με δεδομένη την απόσταση της βάσης από την Τουρκία η υπόθεση είναι ότι θα χρησιμοποιηθούν βαλλιστικοί πύραυλοι Bora (υψηλής ακρίβειας) με CEP 50 μέτρα και μοναδιαία κεφαλή.

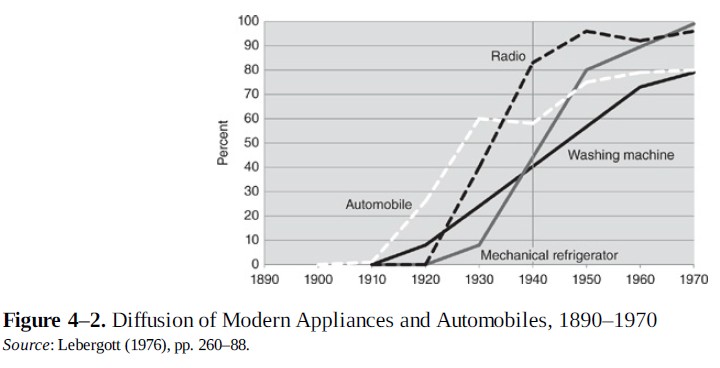

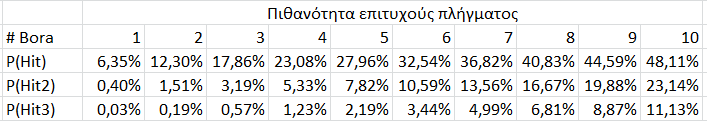

Οι υπολογισμοί των πιθανοτήτων πλήγματος σε 3 σημεία αναλόγως με τον αριθμό των βαλλιστικών πυραύλων που θα χρησιμοποιηθούν έχουν ως εξής:

Είναι σαφές ότι η μικρή ακρίβεια του Bora συνεπάγεται την πλήρη αδυναμία του να χρησιμοποιηθεί για σημειακά πλήγματα ακόμα και σε μεγάλους αριθμούς. Ακόμα και η χρήση 30 πυραύλων για μία αεροπορική βάση έχει ελάχιστη πιθανότητα να επιτύχει την παύση των αεροπορικών επιχειρήσεων από αυτή (αν και σημαντική πιθανότητα επίτευξης πλήγματος σε ένα σημείο).

Ενδιαφέρον έχει η διαφορά στην απειλή από τη χρήση συστήματος (από τις Ελληνικές ΕΔ) όπως το Ισραηλινό Lora με ακρίβεια CEP (μόνο) 10 μέτρων. Σε αυτή την περίπτωση δύο πύραυλοι είναι επαρκείς για να επιτύχουν πλήγμα με πιθανότητα >96% ενώ περίπου 10 πύραυλοι επαρκούν για να σταματήσουν τις αεροπορικές επιχειρήσεις σε μία αεροπορική βάση. 3 εκτοξευτές λοιπόν (με 4 πυραύλους ο καθένας) μπορούν να χρησιμοποιηθούν εναντίον ενός αεροδρομίου ενώ μία μοίρα 18 εκτοξευτών είναι ικανή να στοχεύσει 6 αεροπορικές βάσεις σταματώντας τις αεροπορικές επιχειρήσεις σε ολόκληρη τη Δυτική Τουρκία (με τοποθέτηση των εκτοξευτών στα νησιά του Α. Αιγαίου).

Από την άλλη, ανάλογοι υπολογισμοί για τον πύραυλο cruise SOM (με CEP 5 μέτρων) εναντίον αεροδιαδρόμου υποδεικνύουν πλήγμα με σχεδόν απόλυτη βεβαιότητα (πιθανότητα 99,6% για πλήγμα σε 3 σημεία). Υποθέτοντας χρόνο 8 ωρών για την επιδιόρθωση ζημιάς σε αεροδιάδρομο και 6 κύριες αεροπορικές βάσεις ως στόχους της ΤΑ, η Τουρκία μπορεί (θεωρητικά) να επιτύχει την καθήλωση της ΠΑ στο έδαφος για 24 ώρες καταναλώνοντας περίπου 60 SOM. Σε περίπτωση που η ΠΑ έχει τη δυνατότητα κατάρριψης μέρους των πυραύλων αυτών με τα Α/Α της μέσα η ανάλογη επένδυση εκ μέρους της ΤΑ αυξάνεται.

Είναι σαφές λοιπόν ότι η απειλή των Τουρκικών βαλλιστικών πυραύλων αφορά κατά βάση αποκλειστικά πολιτικούς στόχους (πόλεις, διυλιστήρια) και χώρους διασποράς των ΕΔ αλλά όχι σημειακούς στόχους όπως οι αεροδιάδρομοι των κύριων αεροπορικών βάσεων εκτός και αν επιτύχει τη σημαντική βελτίωση της ακρίβειας τους. Από την άλλη, οι πύραυλοι cruise της Τουρκίας είναι ένα πραγματικό όπλο πρώτου πλήγματος το οποίο θα γίνει ακόμα πιο απειλητικό με την ενσωμάτωση του σε εναλλακτικές πλατφόρμες εκτόξευσης όπως τα UCAVs Akinci.

Η ΠΑ είναι απαραίτητο να επενδύσει στην αυξημένη Α/Α προστασία των κύριων βάσεων της αλλά και στην επαύξηση του δικού της αποθέματος στρατηγικών όπλων καθώς είναι σαφές ότι η χρήση τους για την επίτευξη αεροπορικής υπεροχής απαιτεί τη γρήγορη κατανάλωση δεκάδων όπλων στις πρώτες ώρες του πολέμου. Η απόκτηση 2 μοιρών Lora θα δώσει παράλληλα τη δυνατότητα στην ΠΑ να εκτελέσει πρώτη αεροπορική απαγόρευση στις αεροπορικές βάσεις της ΤΑ με μεγάλη πιθανότητα επιτυχίας. Παράλληλα είναι χρήσιμο ο ΕΣ να παρακολουθεί τις εξελίξεις του PrSM που θα εξοπλίσει μελλοντικά τα MLRS με πύραυλο μεγάλης ακρίβειας και βεληνεκούς άνω των 500 χιλιομέτρων.